Art without heroes, the Mingei exhibition at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow

The “Art without heroes”, Mingei exhibition runs from 23rd March 2024 through 22nd September 2024 at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow.

Please support the William Morris Gallery by visiting the exhibition if you can. I like to put up these posts for readers that cannot get to London to see these exhibitions. Thank you for your interest.

The Japanese word “Mingei” means “folk craft” and is a shortened version of the phrase “minshuteki kogei” which means “crafts for ordinary people”. It was coined by the art critic and philosopher, Yanagi Soetsu in 1925 alongside potters Hamada Shoji and Kawai Kanjiro. The movement found beauty in hand-crafted, every day objects made with natural materials by anonymous crafts people, “Art without heroes”.

It was a movement that celebrated ordinary items in day to day use. It drew its inspiration from many sources, including Zen Buddhism and William Morris’s Arts and Crafts Movement.

The catalyst for the movement was the rapid industrialisation and Westernisation of Japan. Yanagi was concerned that these societal changes were at risk of destroying the folk craft traditions of the country. The Mingei movement was intended to refocus people’s attention on the traditions and values of every day craft objects and the connection between the objects and the people that made them, “the heroes” of Mingei.

Traditional painted wooden Kokeshi dolls

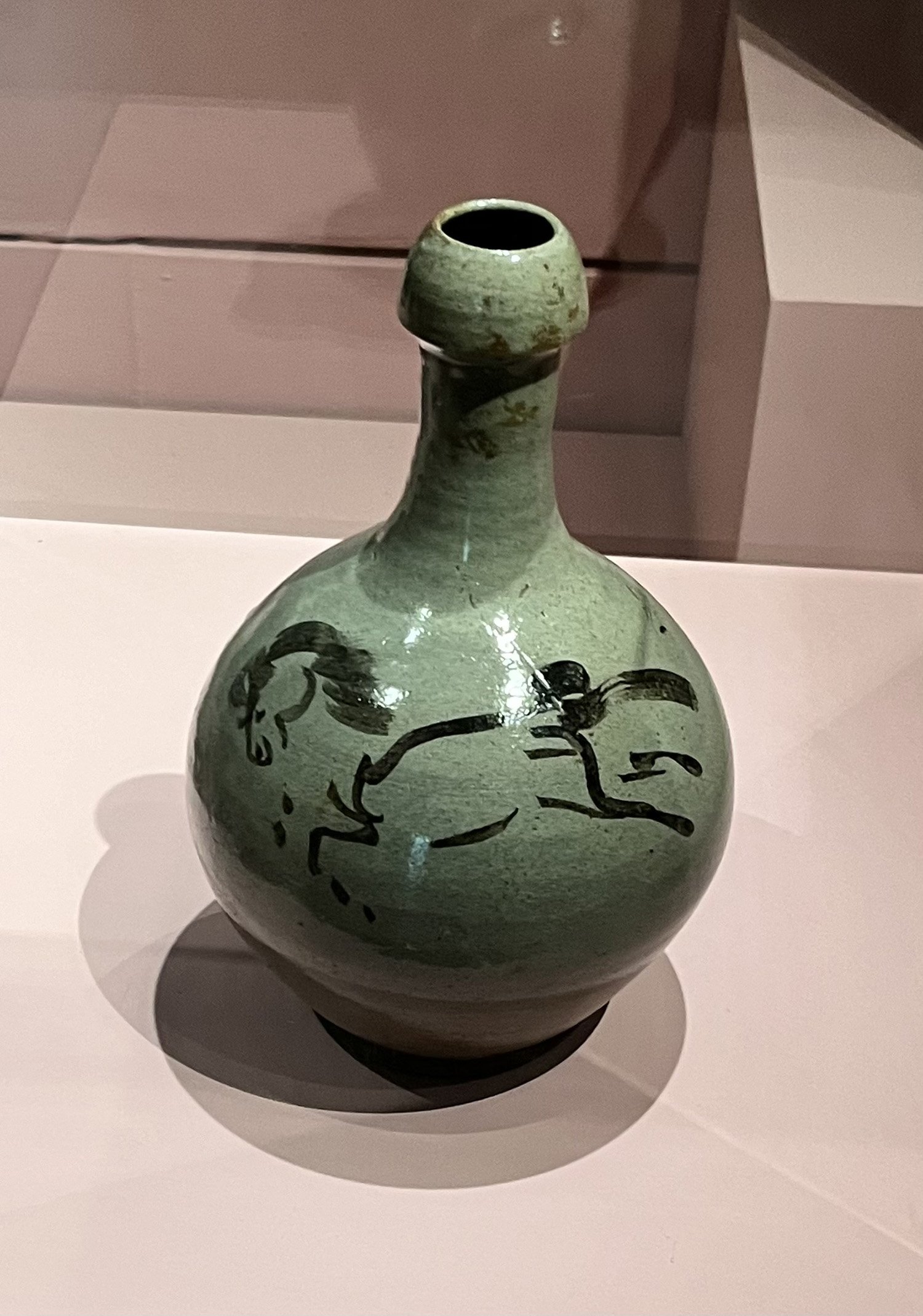

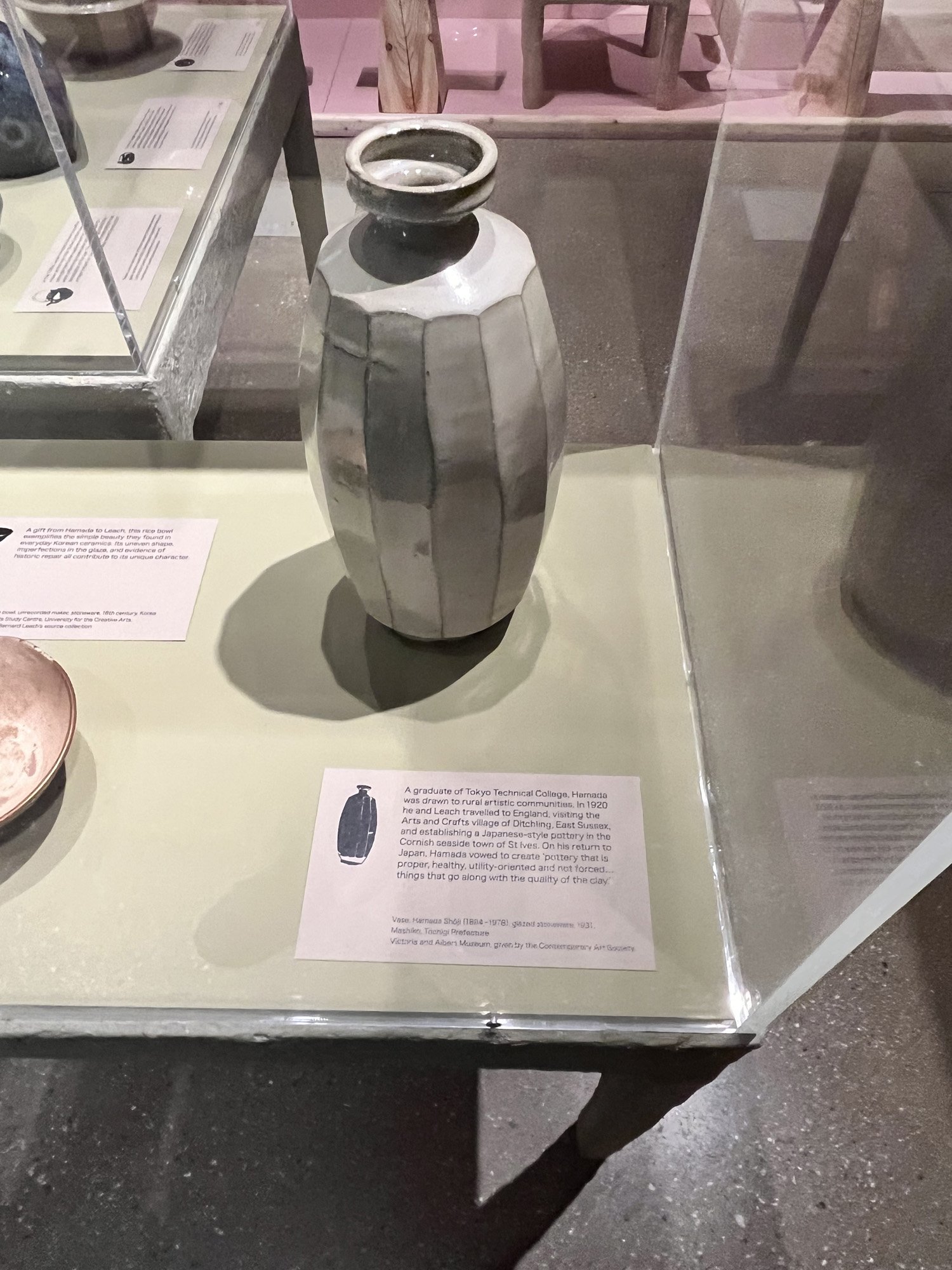

Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada were close friends and exponents of the Mingei philosophy. Hamada visited Ditching Museum in Sussex and worked with Bernard Leach and, with him, was responsible for setting up the Leach studio pottery in St Ives in Cornwall in 1920. Hamada’s sons continued his traditions in Japan.

Mingei objects included simple, every day pottery items, clothing, and wallhangings; items that were made by local craftspeople for use in daily life. They were not “art’ although pieces have since gained a value and appreciation, especially textiles pieces such as “Boro” clothing and bedding that was originally made out of necessity by the very poorest farming folk in the cold parts of Northern Japan.

Boro jacket and child’s Shibori jacket

Boro jacket rear view

Boro quilt

Tabi, Japanese shoes, with Sashiko embroidered stitching

If you’d like to know more about the history and traditions of Boro mending and to learn some traditional techniques to mend an item of your own clothing, click on one of the buttons below to book a class (Online and in person classes available).

Indigo was a much used dye in Japan as it grows readily in the country and was traditionally used to dye fabric for hundreds of years. It was ascribed with all sorts of beneficial properties including being insect and snake repellent, and fire retardant. Many fabrics were resist dyed using “Shibori’, a textiles art that compresses fabric using stitching, binding, folding and clamping and pole-wrapping techniques. You can see a nice example of a child’s kimono at the exhibition.

Child’s Shibori resist jacket dyed with indigo

Country crafts such as Sashiko embroidery were used to decorate fabrics. Despite being beautiful, the dense stitching had a very practical purpose, to strengthen garments made from scraps and to add a layer of warmth from the density of stitching. Boro fabrics could be patched repeatedly over many years and fabrics were often recycled into other uses once they were no longer usable for clothing.

Densely stitched Sashiko jacket

Shibori jacket - back. Kakinohanazashi pattern

Detail of Sashiko jacket back

Aso na ha hemp leaf patterned Sashiko jacket, white thread on indigo cotton

There are two types of traditional Sashiko embroidery - Moyozashi or “pattern” sashiko where patterns are made of a repeating motif and the stitches never touch each other, and Hitomezashi or “one stitch” sashiko where patterns are stitched onto a grid and the stitches meet to create the patterns. If you’d like to find out more, join me for a class.

Using stencils to make decorative work was practiced in the South West of Japan in Ise and in the Okinawa region, where colourful pieces of great beauty, both clothing and art were made.

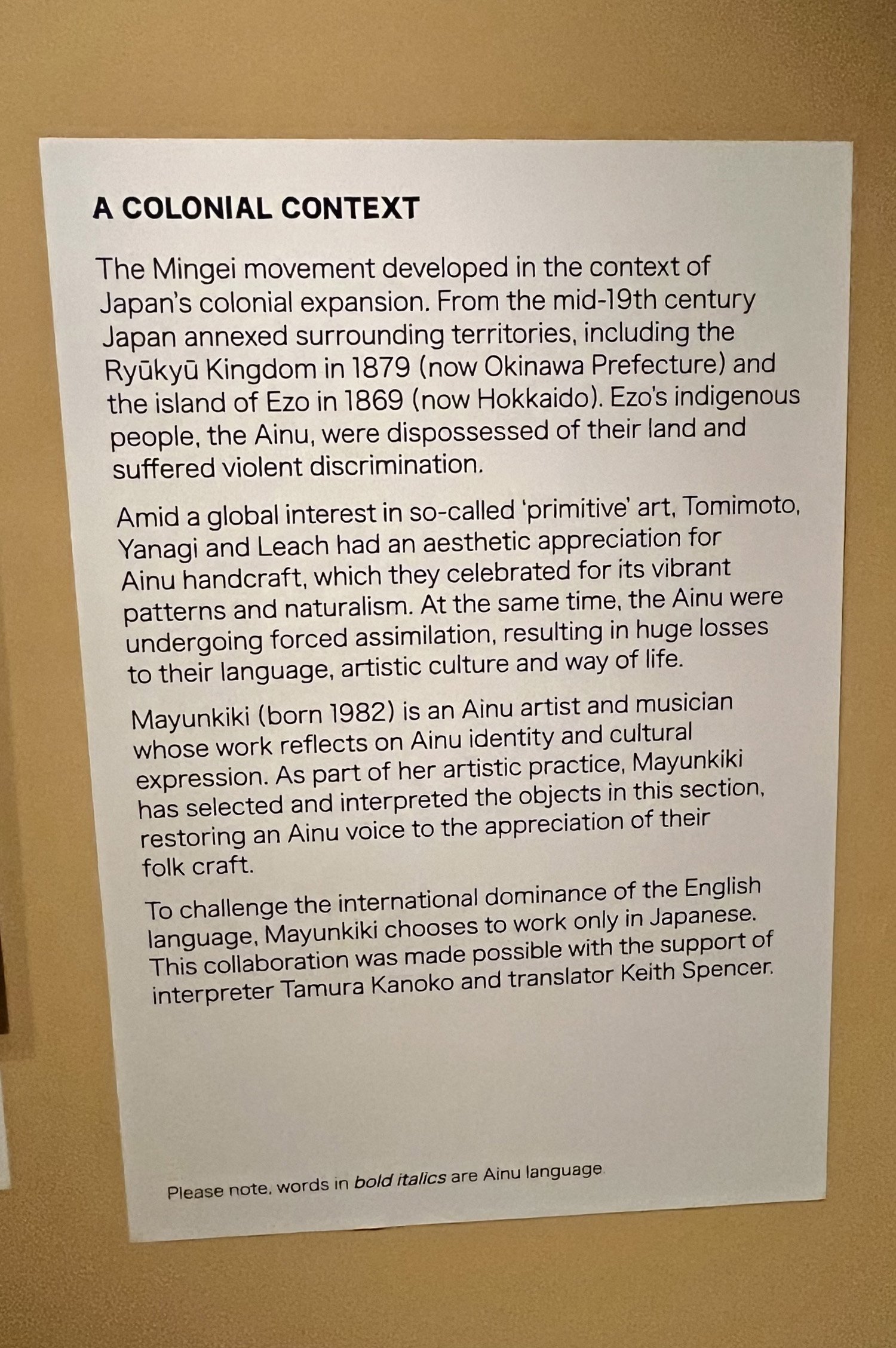

In 1879 Japan formally annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom, which became Okinawa Prefecture. This sub-tropical area was home to the beautiful craft of “Bingata”, using stencils with bright colours to create art and clothing. This screen shows a map of the region and its crafts and is by Serizawa Keisuke (1895-1984), c. 1940

Stencilled resist “Bingata’ cotton robe, unrecorded maker, 1800-70. Bingata robes like this one were worn exclusively by the Japanese royal family.

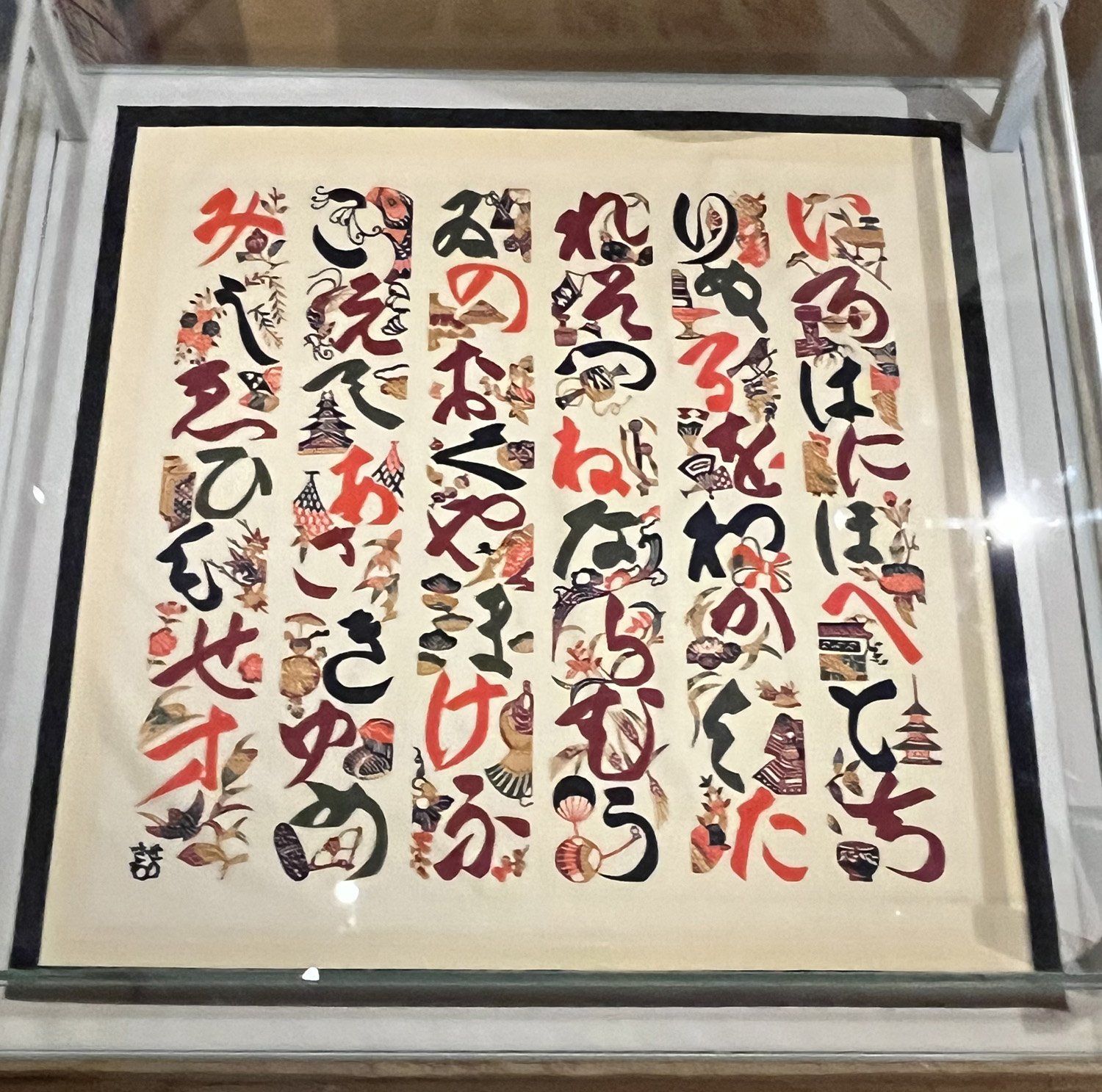

This stencilled, resist dyed Furoshiki (wrapping cloth) depicts a classic poem that uses all 46 characters in the Japanese hiragana syllabary. On silk, 20th century, by Serizawa Keisuke (1895-1984)

Katagami (stencil cutting) and Katazome (dyeing using stencils) are artisan crafts in Japan with a long history. Bingata stencils were typically used with coloured plant dyes to produce bright and bold fabrics but the Katazome traditions used a rice paste with indigo to make beautiful and complex repeated patterns for elaborate kimono. If you’d like to find out more, why not spend a day with me in my studio in Muswell Hill? You will cut your own small stencil from authentic Japanese Kakishibugami stencil paper, learn to make the traditional rice paste and stencil fabric using your own and my modern and vintage Japanese katagami stencils. All tools and materials are provided.

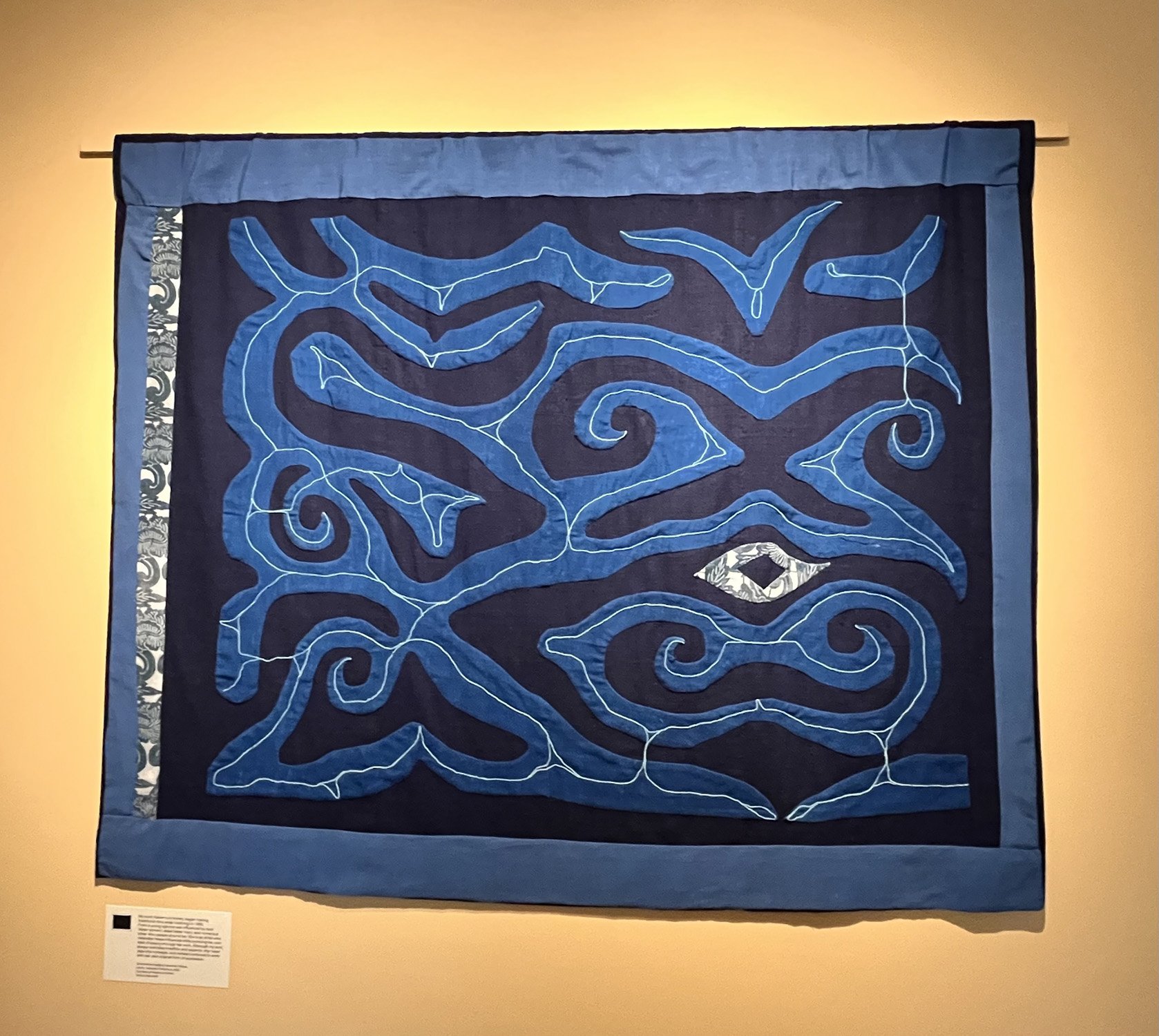

The Ainu are the indigenous people of Hokkaido, a large Japanese island to the North of Japan’s main island, Honshu. The Ainu people lived off the land, making use of all the natural materials at their disposal and would trade with visitors for items they could not make themselves. Their arts and crafts have a particular style. If you are interested to find out more about them you can watch a virtual exhibition of the recent “Ainu Stories” exhibition that was on at Japan House in London in Spring 2024.

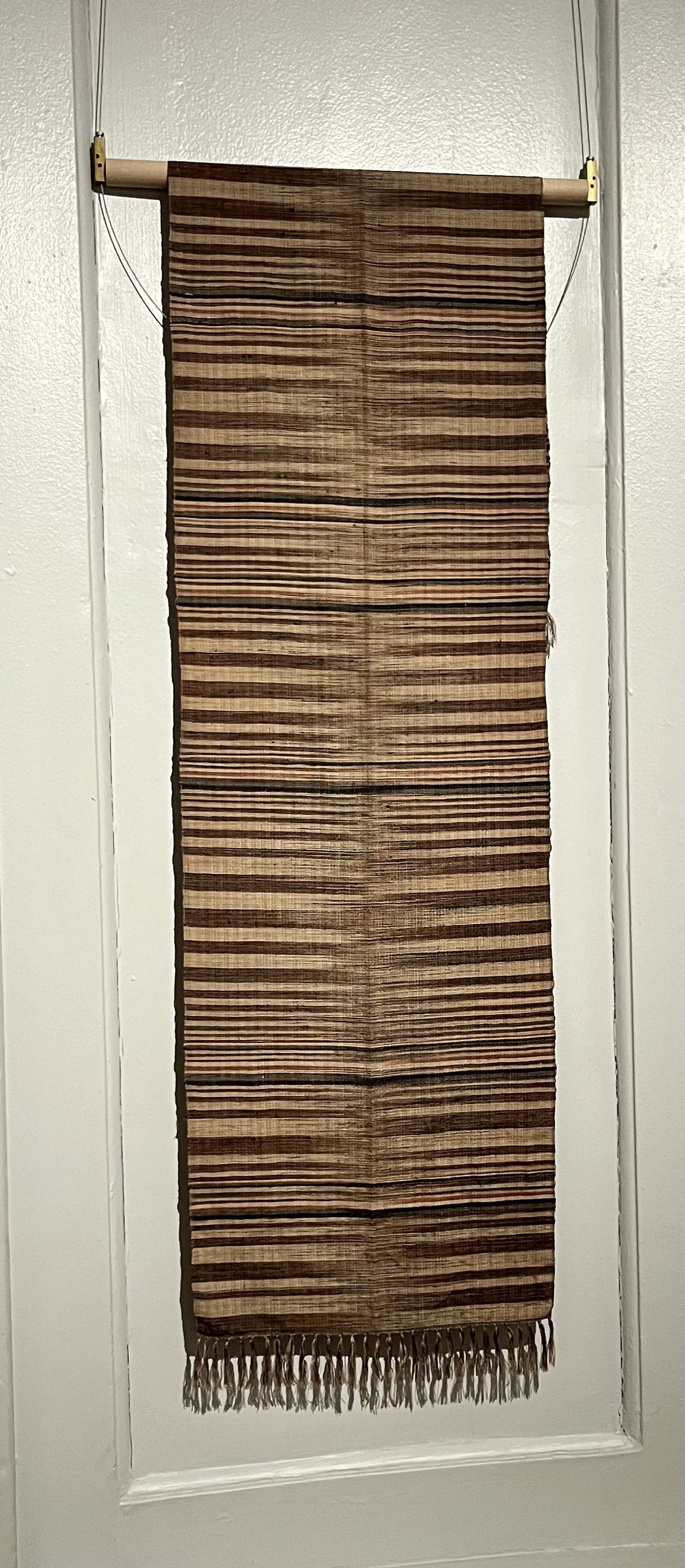

Ainu wallhanging

Ainu jacket

Woven wall hangings

The principles of Mingei teachings and ethos have carried on into modern day Japanese designs, with functional but aesthetically pleasing every day work being made by modern designers in Japan. See captioned image below the main picture for more information about these modern designs.

Modern Mingei pieces

If you have enjoyed this post, please leave a comment and pass on to any friends you feel would be interested to read it.